Frieze

Denzil Forrester’s Brixton’s Blue

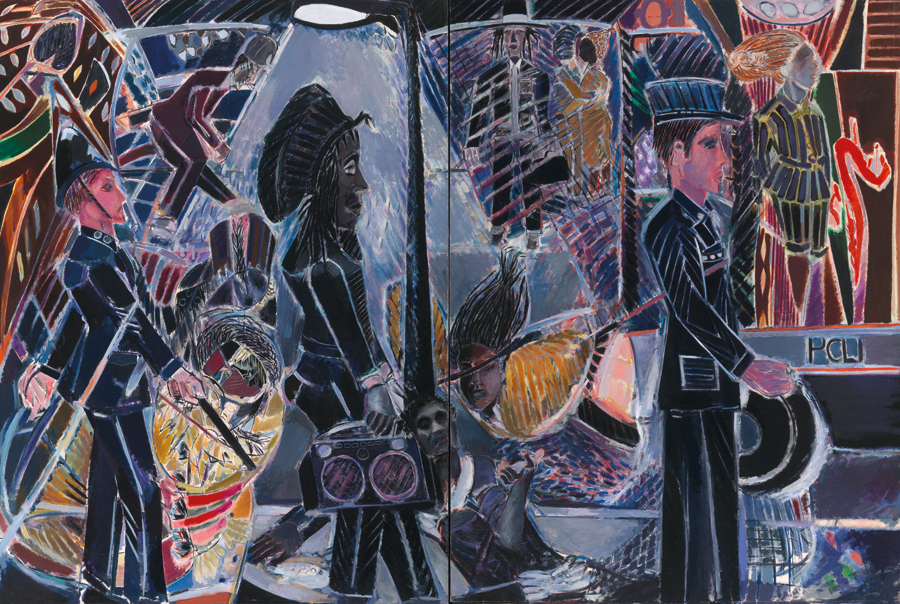

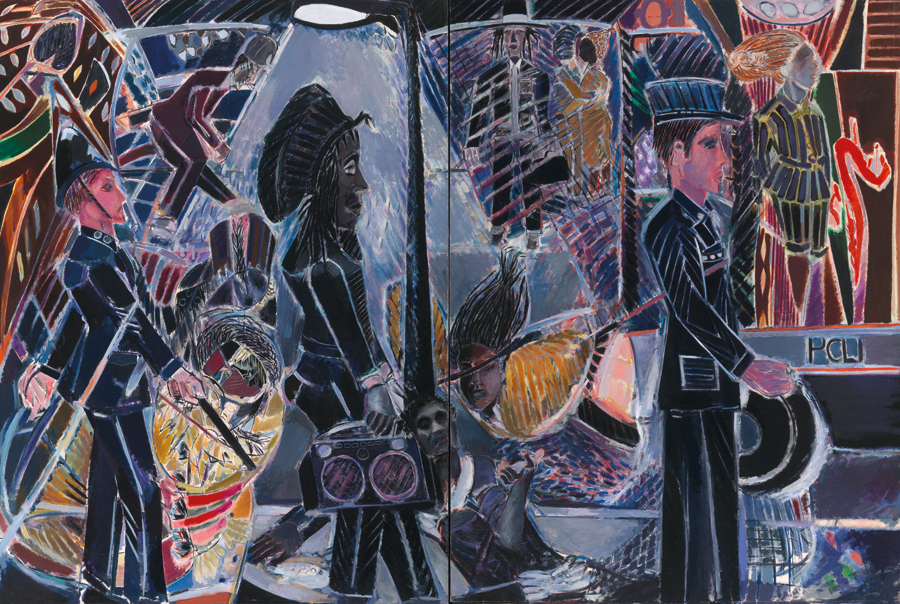

A policeman wielding a truncheon, a Rastafarian holding a portable sound system and a suited politician appear in Denzil Forrester’s Brixton Blue (2018). The mural is the Grenada-born artist’s latest reiteration of his seminal painting Three Wicked Men (1982) and is situated in the entrance to Brixton Underground station. Commissioned by Art on the Underground, the work is everything the title suggests — it reflects the history of the South London district in deep, nocturnal blue-purple tones. Like much of Forrester’s work, Brixton Blue (2018) is a comment on the two contrasting sides to the African-Caribbean experience in London; from being in the centre of dancehall to the centre of police surveillance. The concept of capturing nightlife and police presence comes from a place of reckoning. A friend of Forrester, Winston Rose, died whilst under police restraint in 1981, a moment that has haunted Forrester’s work throughout the decades. ‘I’d drawn a lot of people falling asleep in nightclubs; one of the people I drew was lying on their back. I imagined Winston’s head on the stranger’s body,’ explained Forrester in an interview in frieze earlier this year. Informed by the prominence of police brutality, ‘stop and search’ and the rising tensions which eventually led to the 1981 Brixton Riots, Forrester’s work documents the atmosphere within the underground Reggae and Dub spaces that Black people inhabited; sombre yet pulsating. You can see how the bright beams throughout the work could be interpreted as either club strobes or flashing emergency lights.

Despite its historical references, Brixton Blue is of today – see the young person capturing the buoyant scene on his smartphone, for example. The work also arrives in the area at a time when its identity appears under threat from gentrification. ‘A lot of the people who would have lived around Brixton have gone now; it is a totally different place – a lot of Black people have been pushed out,’ explains Forrester. Brixton is not a place shy of bright and joyous murals, however, and Forrester’s work beautifully pictorializes an unpalatable story of injustice and how a community had no choice but to dance in spite of political angst and discomfort. As many defining stories are slowly fading out of memory and existence due to rapid property development, it’s crucial to find ways to add back in lost colours, characters and context; something Brixton Blue does without hesitation and before the eyes of the many commuters who will enter the station.