The Observer

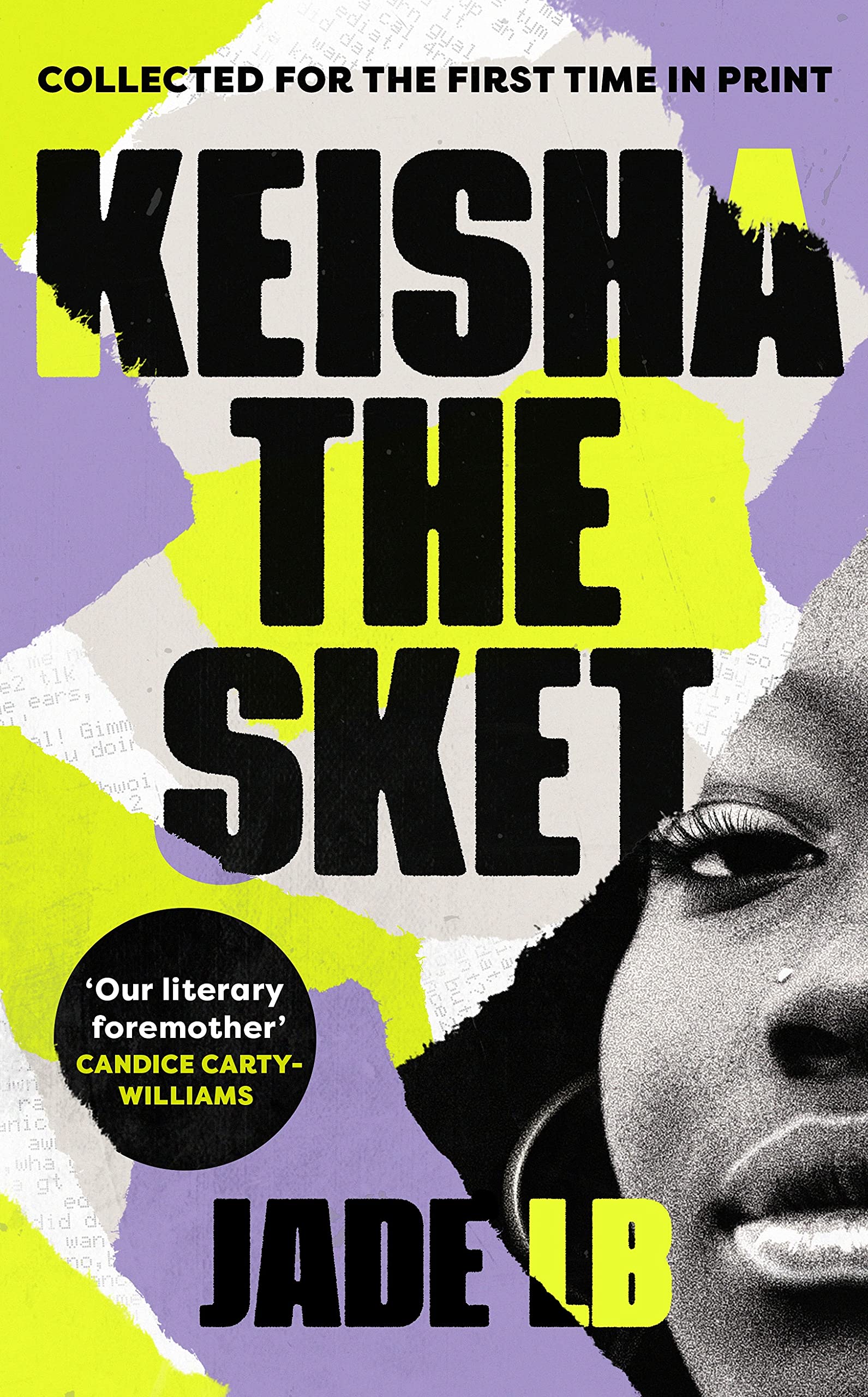

Keisha the Sket — Jade LB

In 2005, the then 13-year-old Jade LB wrote Keisha the Sket (originally called Keisha Da Sket) – a sprawling narrative about a 17-year-old girl from inner London whose life consists of sex, predatory men, parties and tragedies. LB uploaded the tale on to a blog site called Piczo and the story spread around London schools before social media was really available on phones. Its appearance was a definitive moment in Black British history. According to lifestyle platform Black Ballad, it “accidentally decolonised literature”.

A raw portrayal of teenage lust, the story, now in print with new chapters, starts with Keisha excitedly planning to meet up with a boy for sex. “Dat sexc bwoi ramel iz invitin me 2 his yard 4 a lash init,” she beams. On her way there, she collects her friend Shanice, whose older brother, Ricardo, flirts with Keisha. They have sex, which LB describes in vivid but unromantic detail: “I took his warm dick and placed it in ma mouf.” Soon, Ricardo and Keisha confess their love for each other, but Keisha’s sexual past haunts her and some local boys spread rumours about her having several abortions. Things turn grotesquely dark when, later, Keisha is brutally gang-raped by the same group. Seemingly, she quickly recovers and she and Ricardo get engaged. But on her 18th birthday, she is kidnapped and raped by college friend Malachi, who becomes violent after she rejects him.

The overlapping of the adultification of Black girls with social conservatism about female sexuality leads to the kind of “misogynoir” that Kesha experiences. LB refers to this in her intro; how Keisha reverts to normal after being gang-raped, because “the world she exists in doesn’t recognise what happened to her as a violation”. Discourse around rape has often excluded Black women, and Tarana Burke founded the #MeToo movement specifically to afford Black survivors the same degree of empathy as other women. Had Keisha the Sket been written today, LB would likely have the language to locate Keisha’s assaults within a wider patriarchal framework, rather than them being isolated incidents attached to her supposed hyper-promiscuity. Even when partaking in her own sexualisation, repeatedly commenting on the smallness of her waist and the bigness of her breasts, Keisha understands that a woman’s purity is her currency. In order to receive love from Ricardo and respect in society, she must slut-shame herself back to virginity. “Ive slept around abit aswel, but ive used protection at least 90% of da tym. I aint proud of da tingz i bin up 2… I wish I cud turn bck da clock.”

The book also includes a revised version of Keisha the Sket written in standardised English. This take adds more context, such as Keisha’s relationship with her alcoholic mother, more introspection, and more scene-building. It features a new, brighter ending, too, in which, after the kidnapping, Keisha ends up getting into university. But what makes the original so stellar is its idiomatic language.

The deliberate reconfiguring of words such as sexy, mispelled as “sexxxxxi” or “sexc”, is, as Candice Carty-Williams writes in a closing essay, “nothing short of revolutionary”. Throughout history, to be a young Black anglophone can be defined by a semantic urge to dismantle formal grammar as an objection to assimilation and respectability politics. Writing in the New York Times in 1979, James Baldwin noted that language is “the most vivid and crucial key to identity: it reveals the private identity, and connects one with, or divorces one from, the larger, public, or communal identity”. These micro radical acts – swapping “the” with “da”, for instance – are testament to the ways in which Black people constantly rework linguistics to bypass white detection and speak directly to one another. The African American-coined “woke” was once a perfect example.

The combining of Black working-class London colloquialisms, Jamaican patois and SMS shorthand created a new dialect particular to 21st-century Black Britons. If you read the OG version of Keisha the Sket and feel nostalgic, you are inadvertently revealing your demographic, your class, your heritage. As Baldwin once wrote: “To open your mouth in England is (if I may use black English) to put your business in the street: you have confessed your parents, your youth, your school, your salary, your self-esteem, and, alas, your future.”

Keisha the Sket is the literary version of the Black nod – a gesture that lets us know we exist to one another, if no one else. While the revised version will mean the story will travel further than the “endz” that first spread the word, the original Keisha the Sket is a rare example of what it means to create for the Black gaze, to write without asterisks.