The Guardian

Untitled, Kettle’s Yard

Six funk, soul and dance record covers by Black singers from the 70s and 80s are displayed in a grid on a wall at Kettle’s Yard. Next to them is a video installation showing the artist Harold Offeh in a domestic setting – an attic, a hallway, a bathroom – recreating the theatrical poses of the sleeve photographs as music plays. He transitions from Melba Moore’s one hand on the hip to Gloria Scott’s two hands cradling each side of the face.

For Grace Jones’s Island Life, Offeh oils himself in preparation to hold the iconic arabesque pose, but he shakes and grapples with the statuesque stretch, losing his balance. Though it subtly comments on the construction of queer, racialised and gendered bodies in pop cultural imagery, Offeh’s Covers Playlist is one of the more playful works in the gallery’s group show Untitled: art on the conditions of our time.

Ten British African diaspora artists come together in a profound display of contemporary artworks. The show isn’t necessarily an exploration of Black British identity, but rather a reflection of and reaction to our times. Naturally, personal identity features in numerous paintings, videos and installations, but the lack of contextual framing allows each work to be encountered on its own terms. Still, there’s connective tissue, through similar understandings of colonialism, sexuality, love and music.

An interest in the everyday informs the works of Barby Asante and Kimathi Donkor. Asante’s sound and video installation To Make Love Is to Create and Recreate Ourselves Over and Over Again – a soliloquy to heartbreak (2020-21) is spread across various corners of the gallery. In the work, women carry out day-to-day activities (walking, braiding their hair, playing basketball) while reciting Audre Lorde’s 1977 essay Poetry Is Not a Luxury. The audio is muffled by their overlapping voices. Though at times frenzied, it’s an empowering chorus reflecting Lorde’s belief that poetry is paramount to the survival of women.

Exploring the everyday has long been a way of making the ordinary feel extraordinary, but there’s something about months of lockdown that has inverted regular activities into apocalyptic scenes. Somehow a solo stroll, as shown in Asante’s work, or a family walking by pastel-coloured lands, as in Donkor’s Idyl of Osun, Ifé and Sango from 2019, feels more ominous than it should.

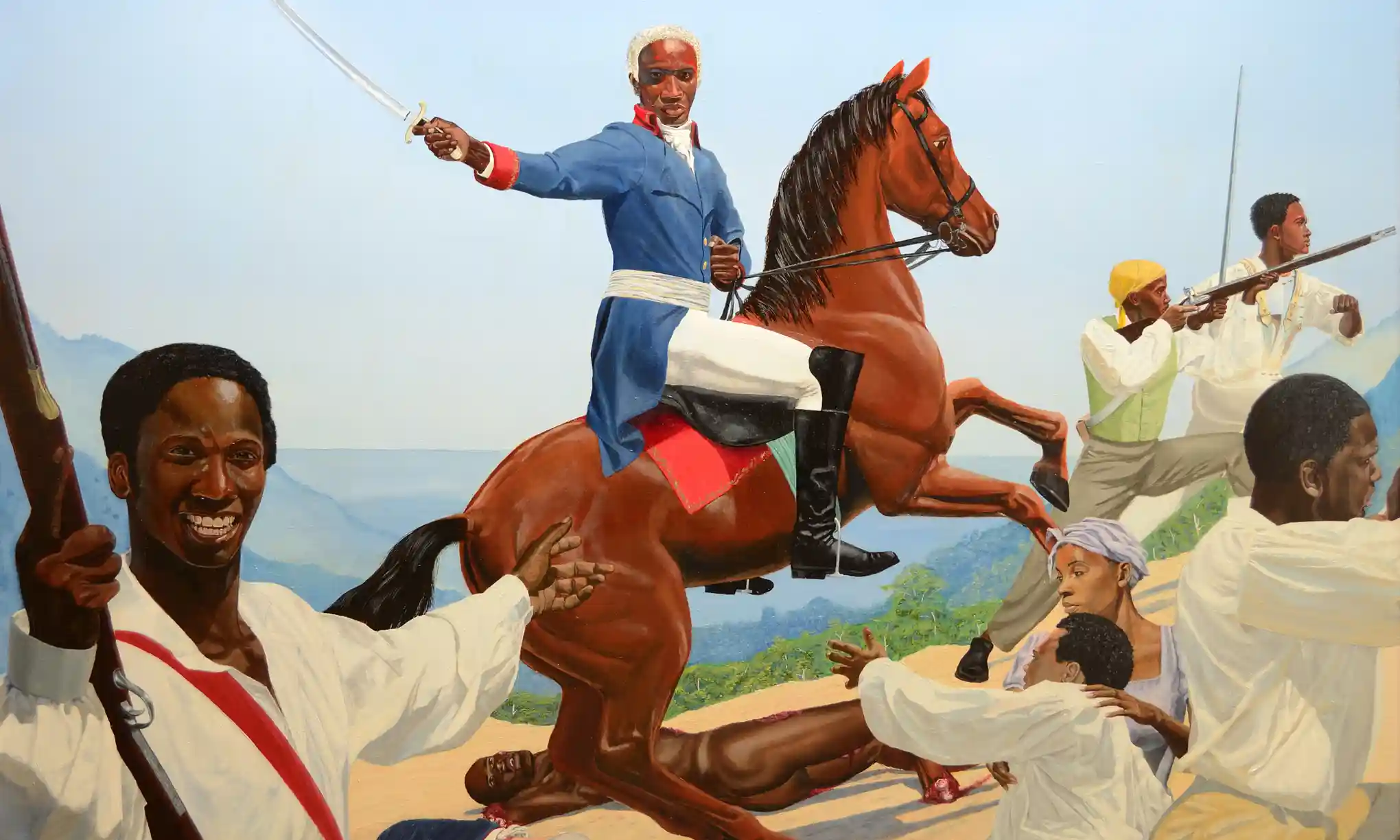

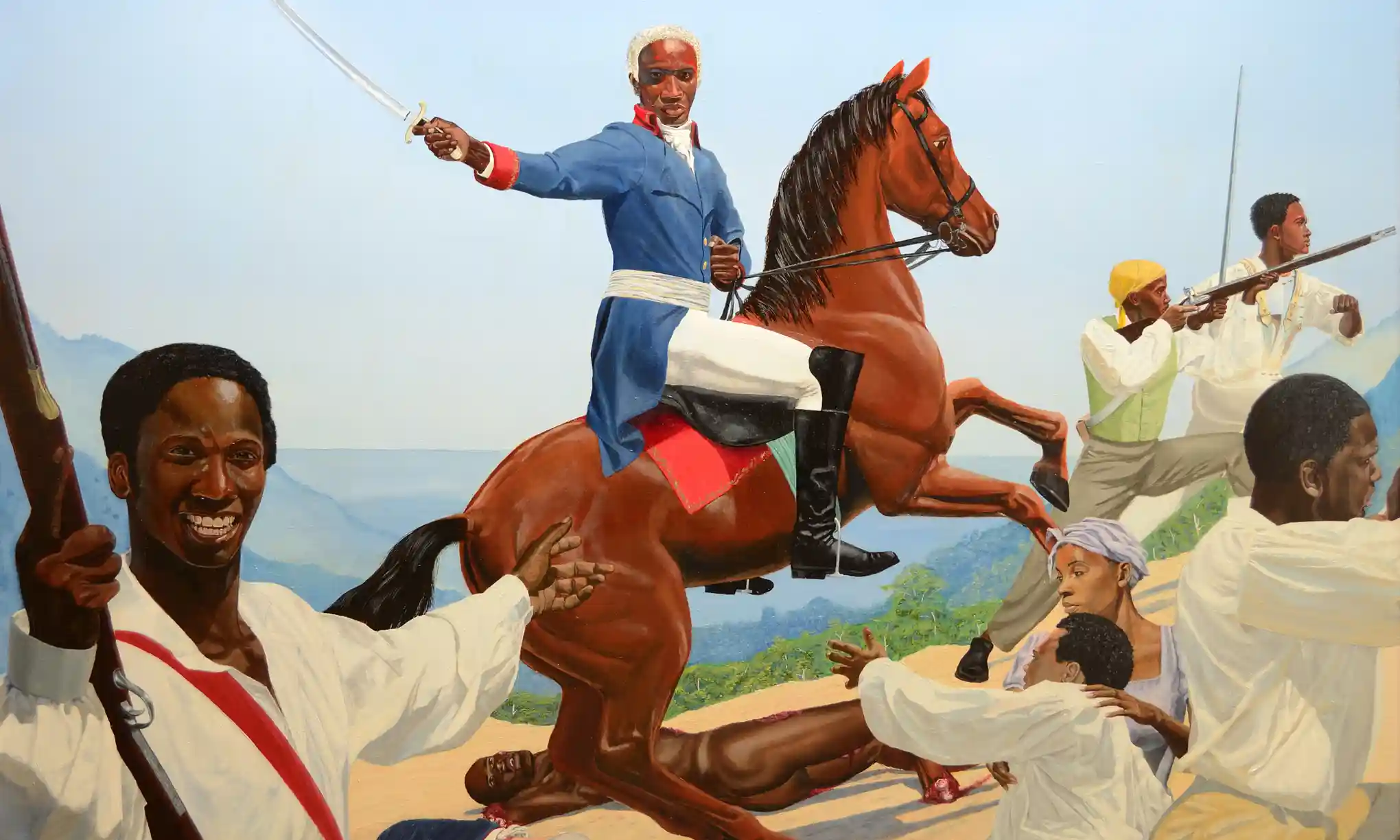

Donkor does overtly explore death in his exploration of African diasporic history. His 2014 work Toussaint L’Ouverture at Bedourete depicts the 18th-century Black leader of the Haitian revolution wielding a sword atop a horse. Reminiscent of Jacques-Louis David’s heroically dashing Napoleon Crossing the Alps, it’s an impressive work of appropriation. Black skin gleams from what is stylistically a European history painting but, more profoundly, this work seeks to illustrate something rarely displayed in public spaces: Black emancipation.

Cedar Lewisohn’s Untitled (Red Woodprints Lewisham series) from 2020 is the highlight of the exhibition. Somehow both delicate and brutal, the comic book of handmade woodcuts and lino prints are collected into an artist publication titled The Marduk Prophecy. He uses imagery taken from African and Mesopotamian civilisations, and mixes them with meditations on contemporary youth culture in the UK such as drill music and the politics around knife crime. Tower blocks sit alongside masonic imagery, Egyptian hieroglyphics and archaic figures lifted from the looted Benin Bronzes located in British museums.

The correlation between these two periods doesn’t feel forced. The image-led book has a non-linear narrative but manages to find parallels in the weaponisation of otherness. While depictions of brutal medieval imagery are ever-present in British museums, the references to violence in UK rap lyrics are constantly being demonised.

Two immersive installations bookend the show. One of them is NT’s Greta, a panoramic film portrait of Trinidad-born dancer Greta Mendez made this year. It shows her surrounded by large exotic plants in the conservatory at London’s Barbican Centre. It might be the least ambitious work in the show, in that it simply aims to celebrate one woman’s beauty, but it’s a moving film nevertheless.

The other is Evan Ifekoya’s Ritual Without Belief, a work from 2019 concerned with Black queerness and community. In a hidden-away room, the installation features an electric, oceanic curved floor and a ceiling populated with balloons. On a white wall hangs a rarely seen photograph, Body Builder with Bra by Ajamu X, from the 1990s. It’s as soothing as NT’s work, but there’s also something unsettling. How can we live, asks Ifekoya, in a place of abundance rather than scarcity? I don’t know. But it is now all I can think about.