The Observer

2021 Liverpool Biennial

There’s a sugary quality to Chiptune — the synthesized electronic music popularised by video game consoles and arcade machines in the 1980s. Hearing it live at the online “listening party” for Larry Achiampong’s series, Videogame Mixtape, is perhaps comparable to eating, as an adult, the confectionery you once binged on as a kid – time is reversed, instantly evoking full-coloured memories of your youth.

Achiampong’s listening party was one of a raft of online events to launch the postponed 11th edition of Liverpool’s biennial art festival: The Stomach and the Port. The British-Ghanaian artist has long been interested in video game storytelling, and his Videogame Mixtape is a meditation on the heritage and evolution of gaming music. The sonic limitations of Chiptune – its 8-bit or 16-bit processors could produce only a small number of sounds – are what gave games like Super Mario Bros their famous blocky and bleepy texture The sounds crossed over into other genres, inspiring grime musicians who sampled and adopted video game soundtracks in their tracks (1994’s Wolverine: Adamantium Rage is said to accidently be the first ever grime instrumental). The piece is also, quite simply, a playlist of “grooves”. Achiampong mixes together glitchy melodies from games such as Sonic The Hedgehog 2 and Street Fighter with accompanying chromatic graphics to be enjoyed as a cinematic compilation album of greatest hits.

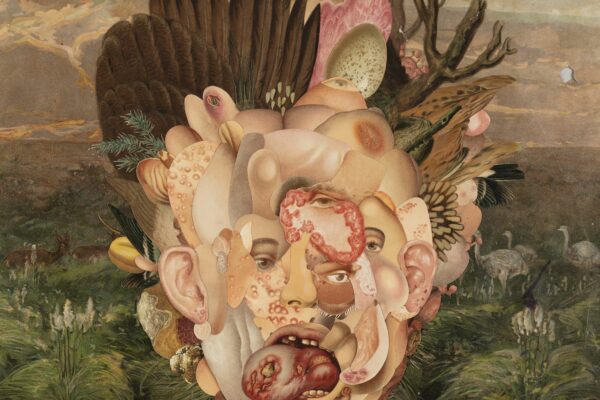

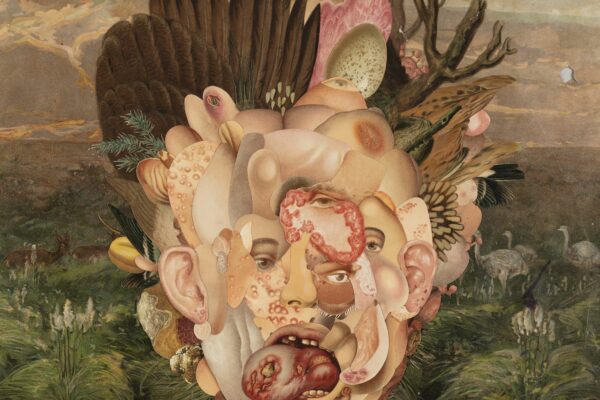

2021’s Liverpool Biennial opens in two phases. The first, last week, included the unveiling of seven outdoor commissions, including a photomontage mural of layered flowers, small animals and red lips by Linder in College Lane, a bronze sculpture of two cast heads by Rashid Johnson at Canning Dock, and, at Exchange Flags, Teresa Solar’s Osteoclast, large sculptures resembling human bones that are made of kayaks. The first phase also features a range of digital commissions, including a podcast series, tutorial videos by body percussion ensemble KeKeÇa, and an AI project – The Next Biennial Should Be Curated by a Machine – by Ubermorgen, Leonardo Impett and Joasia Krysa.

This last is hosted on the“artport” of New York’s Whitney Museum, which co-commissioned the project, and explores the idea of art curation using artificial intelligence. As you enter the online portal, dozens of wheels spin on top of animated psychedelic and sci-fi backdrops. Clicking on the wheels reveals different universes (there are 64 in total), each soundtracked by a TikTok playlist and a pop-up window of biographies of imaginary artists, curatorial statements, press releases, and reviews that continuously rewrite themselves, creating different but similar versions.

One universe features several imaginary artists who share the last name Sibanaz. Jenice Sibanaz (b 1942, Barabinsk, Russia) is an artist living and working in New York, while Waniya Sibanaz (b 1928, Pomigliano d’Arco, Italy) is one of the most gifted artists in the history of tattoo parlours, and Crislynn Sibanaz (b 1961, São José de Mipibu, Brazil) creates sculptures using only her body. The subtle changes in the parameters of the machine-learning process (using data from Liverpool Biennial and the Whitney) generates various possible “biennials”, but with each iteration depicted as pieces of text rather than artworks.

The idea of machine curation might seem otherworldly but it’s already very much a thing. Tate Britain’s 2016 project Recognition used an AI program to match artworks with up-to-the-minute photojournalism, while the 2022 Bucharest Biennale will be curated by an AI programme called Jarvis. The Next Biennial…’s flashy digital collage is more of an entertaining expedition merging pop culture with exhibition literature than a serious investigation into the implications of AI. But still, it’s useful to explore the idea of excluding human decision-making from art curation: after all, the human version has given us a world of shows still heavily biased towards white men.

“Me? I’m not a vegetarian. Never really thought about meat until Covid came along,” a voice says in Meat, the first episode of a five-part podcast series titled Transmission. “Of 25 US counties with the highest per-capita number of Covid cases, 20 have a meat-packing plant or a prison, where the virus took hold and spread with abandon and leaked into the community.” A collaboration between essayist and performer John Barker and Austrian artist Ines Doujak, Transmission delves into corrupt practices in meat production and also looks into disease, class and vaccines “in the distorted world”. Spoken word, music and songs are woven into stories relating to the history of pandemics. In the final episode, Vaccine, a choir sings: “You breathe on me, you sneeze on me, you penetrate my fortress.”

Transmission turns historical violence into a kind of opera. Instances of dehumanisation against migrants, minorities and the poor become high-pitched jaunty ensembles, a comment perhaps on the carefree germy European colonisers who hopped from land to land. But underneath the playfulness, the podcast attempts to connect the dots between past and current conditions. The captain of a slaver ship who threw 131 Africans overboard in 1783 and later claimed maritime insurance for the loss of cargo is linked to Leicester in 2020, when the reason given for the city going into lockdown was its populations’s non-compliance with social-distancing rules; in reality, the high infection rate was a result of the atrocious conditions of the city’s sweatshops. Art as a tool for enlightenment.

Works by Judy Chicago, Martine Syms and Haroon Mirza will go on show in Liverpool galleries once they reopen in May, but the biennial’s early, mostly digital phase, is a timely exercise. We might still be in the beta stage of online exhibitions, homesick for white walls, but digital art is booming. A Jpeg file by artist Beeple (Mike Winkelmann) sold for more than $69m earlier this month. Podcasts, algorithms and webcasts may not be traditional art forms but, as we spend more time at our computers, they can elevate our online experience – and integrate contemporary art into our daily lives.