The Observer

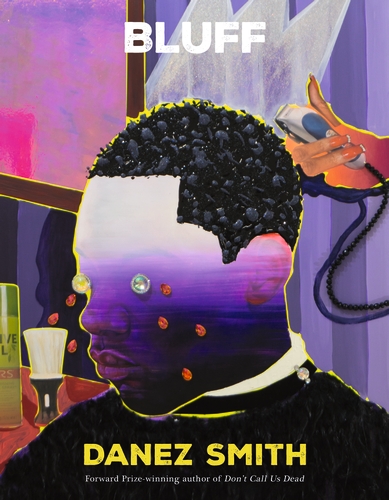

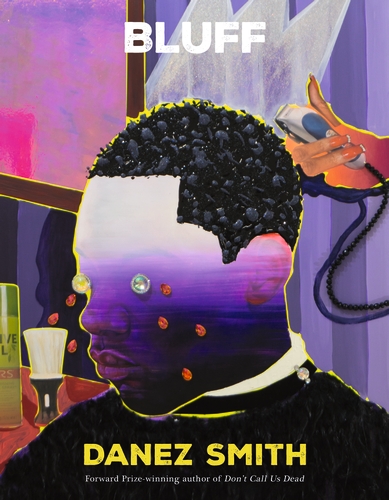

Bluff — Danez Smith

Danez Smith is one of the most important American poets of our age. Bluff is the non-binary author’s fourth collection and, as Smith said in a recent interview with author Alexander Chee, it asks a very specific question: “Bitch, what is poetry?” Is it an individualist project or a tool to aid the liberation of oppressed peoples? Whatever the answer, Smith is clear about what poetry cannot do. “There is no poem greater than feeding someone,” the first verse, anti poetica, begins, one of three poems with that title in this book.

Bluff is largely located in Minneapolis, Minnesota. It is Smith’s home town and where George Floyd was murdered in 2020. The author takes us through the events and protests that followed Floyd’s killing in the expansive reportage-style poem Minneapolis, Saint Paul. Smith reflects on the chants, the rain, the Target store that was set on fire. They ponder the aftermath of the protests, the destroyed neighbourhood, the uncertainty of what will be rebuilt in its place; the faux solidarity performed by a nearby brewery that “put up a 8in x 11in printer paper picture of George Floyd up in their half-block of floor-to-ceiling windows I’ve never seen one of us inside”. The poem bulges with questions. “What America are you mourning”; “Why do we have police?”

If Smith’s Forward prize-winning collection Don’t Call Us Dead (2018) imagined a world in which Black people were free and safe from state violence and white supremacy, Bluff explores what happens when you wake up from that dream. Smith is now sceptical of the world they once yearned for, in i’m not bold, i’m fucking traumatized asking: “is the nigga who raped me gonna be in a thug mansion too?”

They speak of their role in building this world, the way they “obeyed its architecture” and “taught its choreography”. Sometimes you forget you’re reading poetry – the lines are unscented, matter-of-fact, which makes you feel you’re eavesdropping on an inner monologue, but the self-criticism does run the risk of sounding self-aggrandising. Through holding themself accountable, Smith inadvertently becomes absorbed in their own power. Still, their candid reflections reverberate far and wide. “We buried my grandpa with an Obama button. Pinned to his lapel. Finally free, we sent him to heaven American.”

In many ways, Bluff is an Afropessimist text – informed by the theoretical framework popularised by Frank B Wilderson III (who also grew up in Minneapolis) – arguing that anti-blackness is so entrenched it is near impossible to eradicate. In the aftermath of the slave trade and colonialism, Black people are still treated as property rather than humans and liberal methods of redemption are mostly futile because Blackness is in a permanent condition of inferiority. While Smith doesn’t give up completely on the idea of liberation (“let us move the mountain”), they recognise the insincerity of promising “somedays” and “soons” in a world in which Black people still face so much dehumanisation. In the poem less hope, Smith explores their pessimism more explicitly. They contend with their own success and how they “made money” from selling optimism.

“apologies. i was part of the joy

industrial complex, told them their bodies were

miracles & they ate it up”

Smith plays with form, structure and design in this collection. There’s a photographic collage. Poems appear in black boxes featuring words freefalling across the page. The piece sonnet is displayed in a series of cartesian coordinate systems. “If I can’t be the freed, let me be the corrosion,” appears on one of the quadrants.

Bluff’s vantage point is dark and original and foregrounds the historical significance of this time of racial reckonings. It’s experiential, existential and perhaps signifies a new era of politically conscious poetry that rejects ideas of individual empowerment in favour of enlightenment.