The Observer

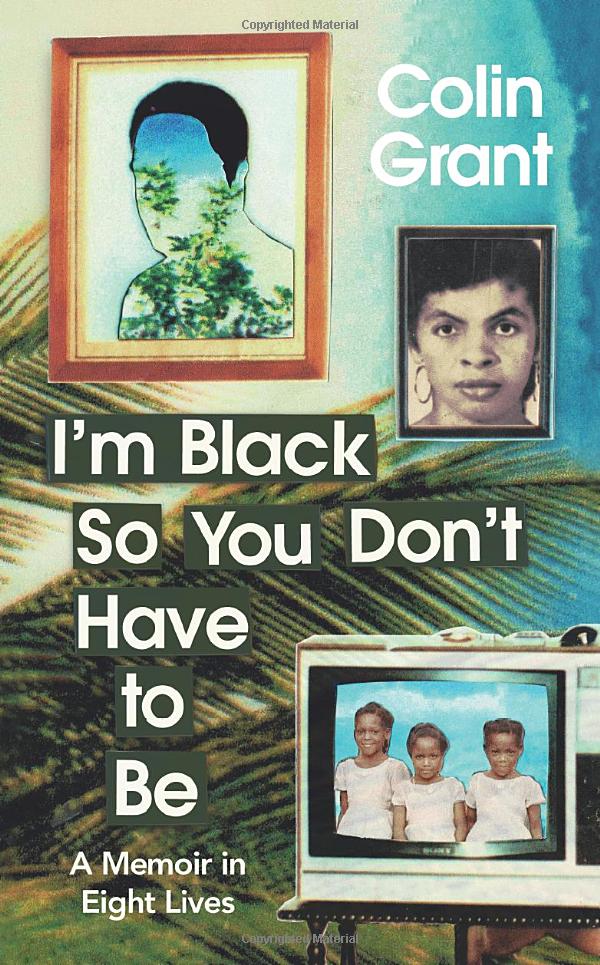

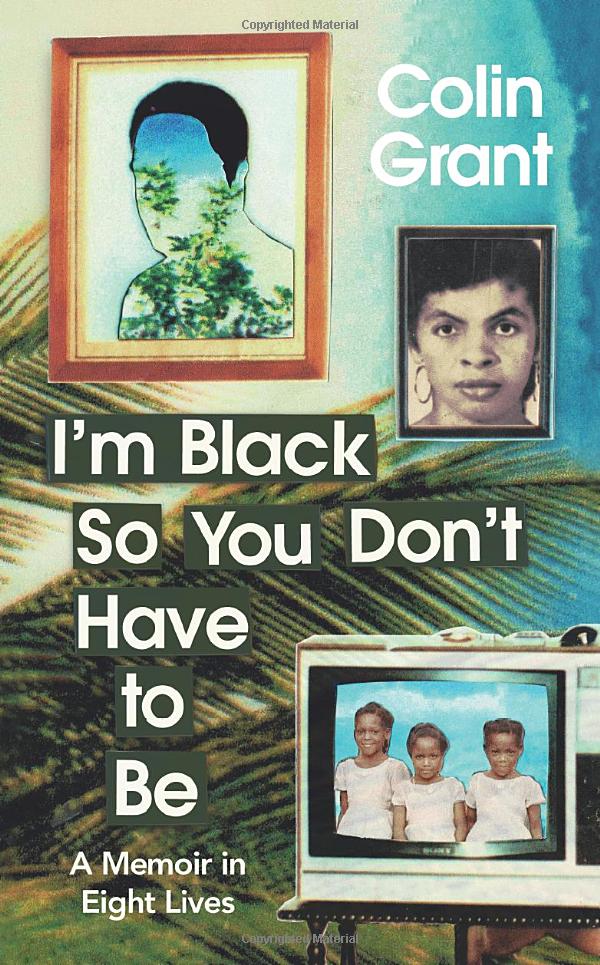

I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be — Colin Grant

At first glance there is something forcibly piteous about the title of Colin Grant’s book, I’m Black So You Don’t Have to Be. It reads as though there is something inherently burdensome about being Black. It isn’t until you read the full quote – “I’m black so you can do all of those white things. I’m black so you don’t have to be” – which comes from his sometime mentor and “ribald philosopher” Uncle Castus, that you understand it is not meant as a display of martyrdom, but rather an insult. It’s a jab at the privileges of the children of the Windrush generation who, hell-bent on being accepted by British society, have left the labour of Blackness to their parents.

Grant, born in 1961 to Caribbean parents, is an author and a former BBC radio producer. This is his seventh book – as well as other memoirs, he has written biographies and oral histories, all of them about Black lives and times. Bageye at the Wheel, his compelling 2012 memoir, was about growing up in 1970s Luton, and this new work offers a broader account of his life in eight absorbing and nuanced chapters; portraits of family members and others, complete with detailed memories, sharp and funny descriptions on British Caribbean ways of living and being, and reflections on the legacy of intergenerational trauma.

Though the book doesn’t open with Bageye, Grant’s “violent” (and now deceased) father, who once pushed his mother down the stairs, he is the constant and primary antagonist whose presence haunts every page. Grant’s regal and defiant sister Selma is the only sibling brave enough to challenge him. Though protective of each other growing up, as adults she and Grant lose touch for no good reason. Grant describes it as similar to a long car journey. “Neither the driver nor the passenger can quite understand how and why the conversation dribbled away into nothingness.” Selma spends much of her youth trying to escape her family and she ultimately does.

While she worked to shed her past, Grant’s mother, Ethlyn, wears hers triumphantly. She fantasised about returning to Jamaica, habitually circling prospective properties in the Jamaican newspaper the Gleaner. Despite living on a council estate in Luton, she long held on to her middle-class status in Jamaica. But the fallacy of memory is apparent on a trip to the island when they pull up to the house she once lived in. Ethlyn is temporarily paralysed at the site of her old home. “The street never used to look like this… it was more suburban. It’s nearly a ghetto,” she says.

Grant’s years working at the BBC connect it to current topical discussions around race. Workplace diversity, unconscious bias and microaggressions have been hot topics since the racial reckoning of 2020, but during Grant’s time in the 1990s, any mention of unfair treatment, he says, would have been categorised as “playing the race card”. He found working there a challenge and – unfairly as he sees it – had several disciplinary hearings brought against him for being “aggressive”.

Key to understanding the emotional landscape of the book is his time in medical school. The years he spent dissecting bodies and dealing with mentally ill patients has somewhat desensitised him to death and feelings. “Always be thinking pathology,” a tutor once told him, and it feels as though Grant has never truly shaken that notion – he often writes about his family with the cold detachment of case studies. There’s an absence of love. Though perhaps that’s the point.

Grant has often chosen silence. He didn’t speak up against his father, or the doctor who asks in front of the entire class why he has a greater chance of being diagnosed as schizophrenic, or the BBC managers who “censor” parts of Jamaican opera singer Willard White’s interview. (He’d been asked whether things have improved regarding Black actors on stage, and responded, “You white people control things. You tell me!”)

But though Grant may bite his tongue in the moment, he does seem to be the kind of man who exacts revenge. The memoir opens with Doc Saunders, Grant’s great uncle who has been exiled from the family for telling lies and for stealing Aunt Anita’s prized violin. Grant goes to live with him in Manor House for a few weeks when he first moves to London for medical school. One night, Doc Saunders says something untoward about Ethlyn. Grant doesn’t respond there and then, but instead opens Saunders’s cage of beloved finches in the middle of the night. It feels that through writing about these people that he knew and the things he has experienced, Grant is redressing and maybe even avenging past injustices. No matter if the moment has passed and the dust has settled; it’s never too late to unlock the cage.