The Guardian

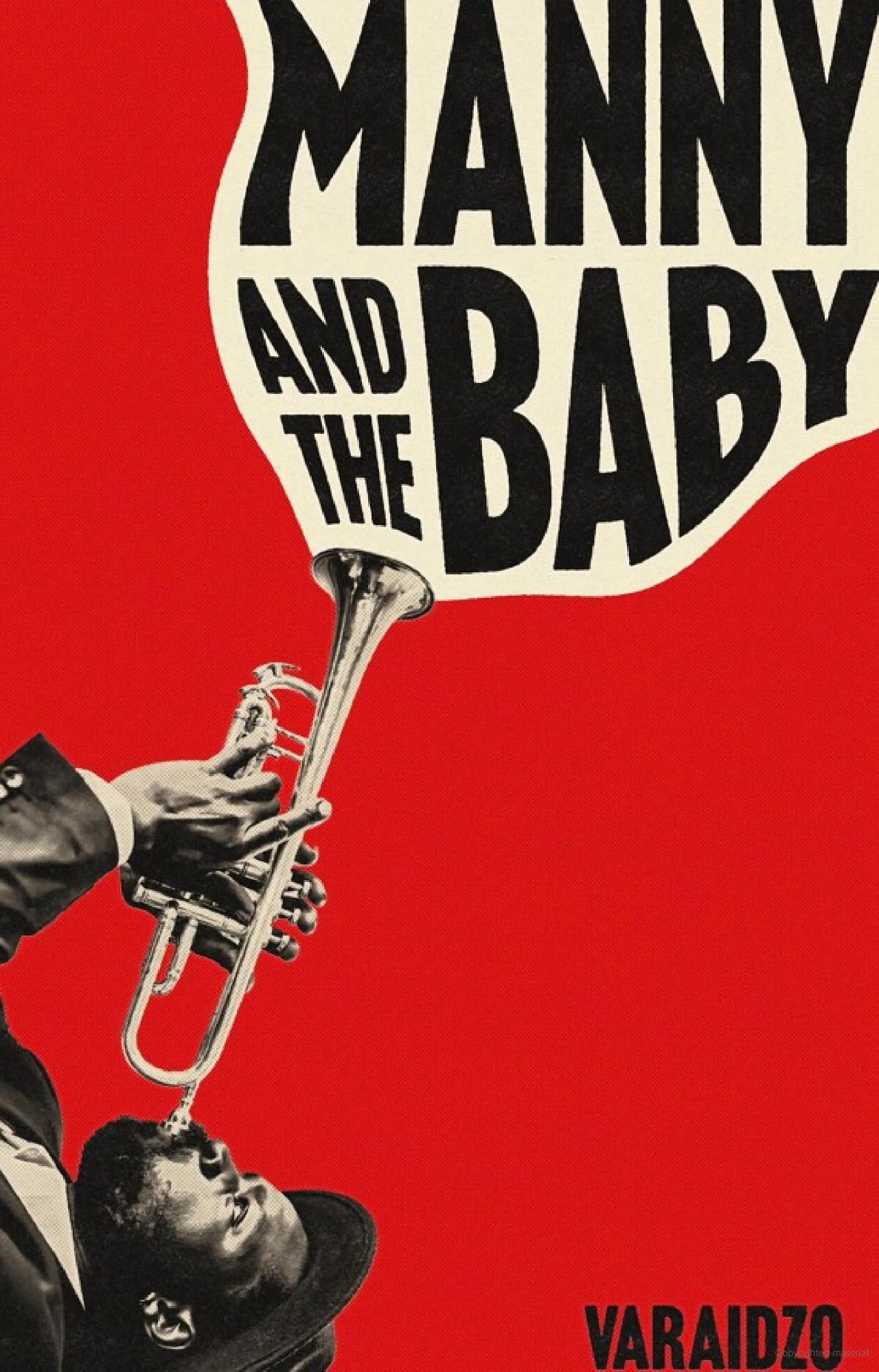

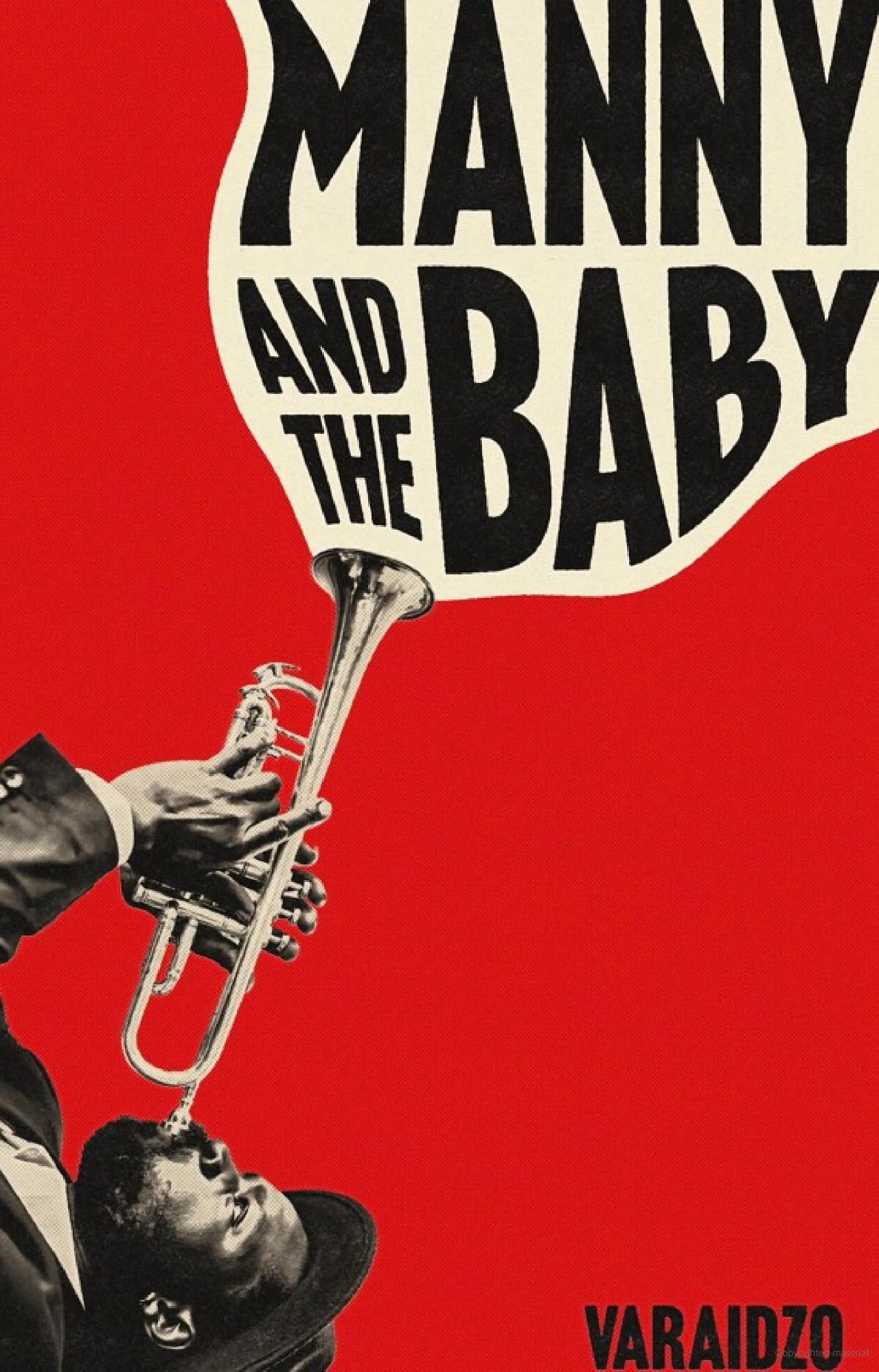

Manny and the Baby — Varaidzo

Set across two timelines, 1936 and 2012, Manny and the Baby is a debut novel about a grieving son, Itai, desperate to connect to his late father through the pile of cassette tapes wrapped in newspaper that he left behind. What is recorded on those tapes leads Itai to discover the fervid history of two estranged sisters, Manny and Rita, and a Jamaican trumpeter, Ezekiel Brown, who all find each other amid Soho’s smoky prewar jazz scene.

The story starts in 2012 against the backdrop of the Olympics. Itai, a proud London boy, travels to Bath to make sense of his father’s death and why he bought a house in a city he had no obvious connection to. “The place was weird. Surreal. Looked like a film set, a cardboard country, begging for him to huff and puff and blow it all down.” Itai perseveres and moves into the property – filling the place with plants and looking through his father’s archive (he was a scholar in ethnomusicology). He buys weed from local boy Josh, a runner and part-time dealer, whose side hustle is at odds with his athletic ambitions.

On the cassette tapes is the voice of a woman called Rita, also known as the Baby, recalling her youth as a dancer. Rita shares her long-ago adventures with budding writer Manny and musician Ezekiel. They dance, write, play and debate. Love brings them together as quickly as it pries them apart. Baby loves Ezekiel, but it’s unrequited – he seems to look at Manny the way she longs for him to look at her. “Ezekiel couldn’t speak. That was the effect I wanted to have on him! I wanted to be so beautiful, so wonderful, so everything, that he was rendered speechless.” It’s a classic love triangle.

Varaidzo tenderly captures the kind of romance shared only between sisters: the doting younger sibling enchanted by the powerful older one. She writes intimate moments between the trio with much charm. At one point, they venture to Bath in search of Haile Selassie, who lived in Fairfield House, “the house of Ras Tafari”, during the five years he spent in exile between 1936 and 1941. In the 21st century, Itai also visits. “The house was the same golden stone as the rest of the city. A statue of a lion was carved in grand stone on the pathway. How could such a man have existed here? How could the so-called black messiah have a home in a town as pale and as white as this one?”

This is a character-driven novel rooted in interpersonal interactions rather than big events, so, although Manny, Rita and Ezekiel are living amid war, fascism and racism, those weighty topics are secondary. But at times, it’s all too squeaky clean, as though the writer grew so attached to the characters, she was unable to let them get dirty. The characters’ sentimentality turns the narrative largely into one long love letter, which does provide some nice moments of poetry, but the slant towards tidy resolutions leaves a dearth of darkness that is needed to balance (and appreciate) all of the light.

Still, there are small moments of tension. When Manny tries to make it as a writer she uses Ezekiel’s name – first with his permission, then later without – to get further in her career. Josh is caught between his affinity with Itai, and the paranoia of his friends, who are convinced that Itai’s presence in Bath is because he’s a Londoner trying to “deal” on their turf. These moments inject brief bursts of energy into a dreamy tale.