The Observer

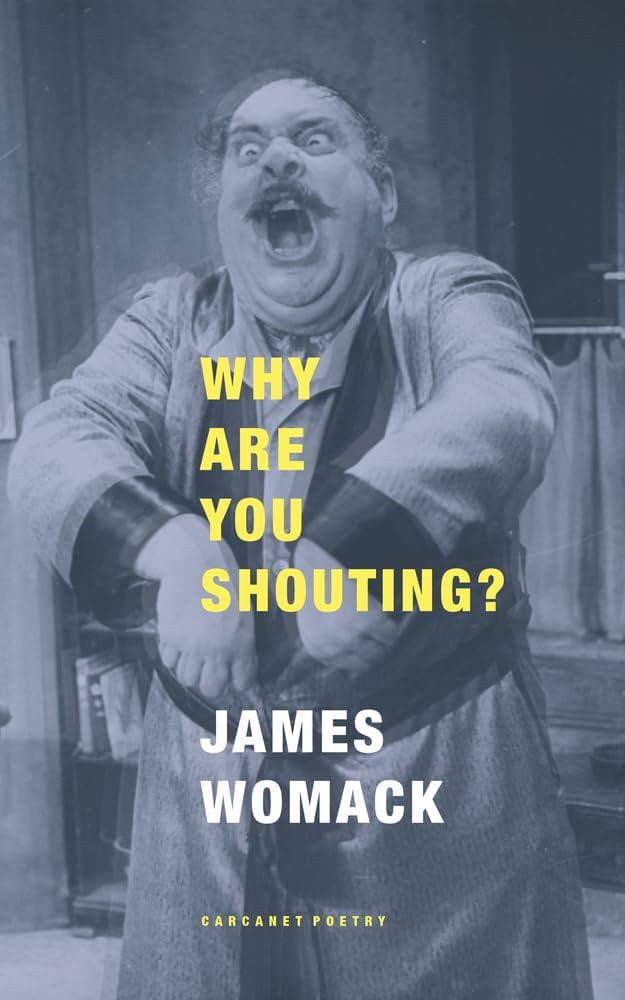

Why Are You Shouting? – James Womack

James Womack’s latest collection sees the city as both muse and antagonist. A frustrated energy merges with sentiment in poems that feel like a last hurrah to living as we know it. “The city is dead, and yes, the country too, / and probably, beyond, the grey wide world,” he declares in Seasons. Womack, the author of three previous books of poetry, wrote this collection in the shadow of climate crisis and the pandemic, which is why it oozes with anguish. But there’s a quietness, too — a sense of acceptance so the poems never blare.

The opener is an epic titled The City, an Argument and sets the tone for an ongoing fraught relationship between place and dweller. The narrator makes bold proclamations that bounce between banal and menacing. “Beloved, the city wakes up after the weekend… / Beloved, the city eats and shits its citizens.” It’s a poem for our times. Here, we see Womack’s affinity with cinema. He generates a landscape of rich visuals that satisfy all the senses.

Womack is an award-winning translator who teaches Spanish and Russian translation at Cambridge University. Thus, the expansivity of language is an ongoing theme, as in The Idyll Replaced By an Unjustifiable Melancholy, in which the narrator describes a picture of a bright Soviet landscape. The English title suggests it’s a picture of a tree, while the Russian version suggests it’s of a field. Womack sees both sides:

“It is say the picture of a single upright stroke in white oil surrounded by dormant & yielding green & yellow oils, & it is say the picture of the field returning on itself with a lonely rowan-tree stiff in the background.” It’s a question of interpretation and how perspective and language are intertwined and can yield different images.

Glimmers of absurdity cut through the more sombre ruminations about war, ruins and poverty. Still, there’s always a pessimism buried beneath the humour. “I looked at the whole magnificent creation of the Lord, and asked, / sadly, ‘Is it cake?’” Womack is smart about how and when he deploys his jokes – too much and the comedy feels contrived; just enough and the humour encapsulates a youthful, shoulder-shrugging apathy.

Sometimes there’s a tendency to overexplain, overshare and lean too much on wordplay in a way that can seem meandering and frivolous. A Short Story, about a night in a cheap, hot hotel room, feels overwrought, while a drowsy befuddlement at times overrides the clarity of his poems. On other occasions, however, his eyes feel wide open. In Room 72, for instance, he yearns so deeply for a lover that he looks for one in the classical statues at a museum: “I try to force my memory of your living flesh to this marble.”

Womack is at his best when talking about love and the search for connection. In Portrait with Hindsight, an ex-partner haunts everything: scents, doorways, the restaurants he visits with his wife. “I am nothing but memory; you are nothing but memories,” he writes, and there’s a beauty in these moments of collapse.

Another epic poem ends the collection, Cassandra, the Trojan princess whose prophecies were never believed. Womack ponders on how it must have felt not to be trusted. To speak with conviction but not be heard. He interrogates his own ability to listen and to distinguish fact from fiction. “So many questions remain unanswered, / but I know I would rather make up an answer than live without one.”

These poems meditate on what it means to live and believe. They are contemporary narratives that consider the failures of the past and the possibilities of the future. Dark times anchor Womack’s writing, but faith remains.